Request 12/97

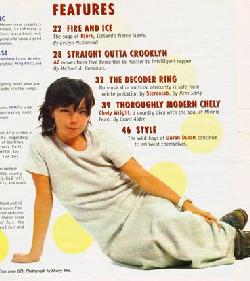

Björk - The Saga Of Iceland's Fierce Faerieby Evelyn McDonnellPhotos: Cherry Kim

|

|

From New York City, Icelandair flies up coast of Canada, over the white glaciers and aquamarine fjords of Greenland, and touches down at Keflavik International, a small airport in a plain of gray frozen lava 30 miles from Reykjavik, Iceland's capital and only city. It's a five-and-a-half hour trip; from London it takes two hours. Before airplanes, the only way to get to Iceland was a several-day voyage by boat. Björk sings a lot about 'aeroplanes', as she calls them. On 'speed is the key', a track on the Sugarcubes' 1989 album, Here today, tomorrow next week, she exalts: "I'm a spacegirl/pass me that aeroplane/I've got to go now/speed is the key". On Aeroplane, from her 1993 album, Debut, she wows, "I'm taking an aeroplane across the world to follow my heart." Björk knows all about the importance of flight. For a dozen years, she's been traveling around the world, first with the punk band Kukl, then with the Sugarcubes, and now as an internationally acclaimed solo artist. Planes have taken her back and forth from London - where she has lived for the last four years, soaking up and wringing out its electric club culture - to Iceland, which she calls home. It was in an airport in Bangkok, Thailand, that she became the center of a world-famous tabloid scandal last year, when she attacked a TV reporter live on the air. And it is the airplane that brings foreign journalists to track down the pop star in her native environment, interviewing her in coffee shops, photographing her at tourist spots, and trying to gain an understanding of Björk and her strange homeland. "I want to be

truthful about Iceland and being from Iceland,"

Björk says. "And I don't

mean Viking helmets and all of that shit.

I was born here in 1965. I was born with raw

nature everywhere, but still brought up with

computers and technology. For a lot of

people, nationalism is a bad thing, because

it's about the past. What's beautiful

about modern days now, all over the world,

is more and more people are having similar

lifestyles.

And because of that, our identity becomes

even stronger, because the opposites meet in

an even more fierce way. I go to London, and

I've never been so Icelandic. When I

lived here, I didn't even think about it.

The sound of the album was an attempt to be

truthful to updating what we are today

and what we sound like." "I am from Iceland.

I was born with two legs, two arms, and genes that go 1,200 years

back being what I am, with my nose, my eyes, whatever,"

she says. "That is Icelandic.

I'm singing in English because I've

chosen to communicate and it's not going to get us

anywhere if I'm singing in Icelandic. So I'm

just being truthful about being a person

who comes from Iceland who's willing to communicate.

I think what's most Icelandic

about this album is, energy-wise, it's

kind of raw. There's a sense of identity I can

hear very strongly in the music. But it's

purely emotional, rather than particular

sounds or noises.

Björk is an international pop star and an Icelandic national treasure. She's perhaps the inevitable, idiosyncratic product of a European country that has finally caught up with the rest of the Western world: well-versed in technology and postmodern beats, still just a little exotic - a representative of a country shaped by fantastic sagas and reputedly populated by ghosts and elves. Yet if Homogenic makes Björk a worldclass surname-only star alongside Madonna and Prince, it will be because it's a deeply personal album. The title refers to Björk's self-production: "I wanted to be able to say it was mine, to be more truthful about what I'm about, who I am." Its 10 songs chronicle a woman going into and coming out of a "state of emergency," as the album's first single, "Joga," puts it. Björk wrote and recorded Homogenic shortly after what she alternately refers to as the "crash" or "kick," a period last year when her jet-set lifestyle went into a nose-dive. It was a long journey down to a safe landing.

At 11, she recorded her first album, Björk, featuring Icelandic folk songs and one original composition. The record went gold in Iceland, people began stopping Björk on the stree, and she decided to go punk instead. She played drums in her first band, an all-girl ouffit called Spit and Snot that "believed boys are crap, they're only good for shagging." She was in a couple of other bands before Kukl formed in 1984 as a sort of supergroup, like the Icelandic punk Asia. Kukl recorded two albums of not-bad experimental political punk before splitting in 1986. Björk and two other Kukl members then joined with three new players to form the Sugarcubes, a B-52's-ish new-wave band whose first single managed to excite the excitable British music press. The Sugarcubes released four albums and toured the world before breaking up in 1992. By that time, Björk already had begun stepping out, singing with 808 State and recording Gling-Glo, an album of jazz and pop standards, with the Trio Gudmundar Ingolfssonar. In 1993 she moved to London and released Debut, an album heavily influenced by that city's happening club scene. Produced by Soul II Soul's Nellee Hooper, Debut yielded hits in both the whimsical pop of 'Human Behavior' and 'Venus as a Boy', and the exuberant dance grooves of "Big Time Sensuality' and "Violently Happy." Björk pushed the hipness factor even further on 1995's Post, collaborating with Hooper, Graham Massey, Tricky, and Howie B in a dizzying collage of techno, show tunes, pop, trip hop, and ballads. She worked with still more artists for 1997's Telegram, an album of remixes of her tunes by a stellar cast including LFO, Dillinja, Outcast, Eumir Deodato, and Evelyn Glennie. Björk was clearly on the cutting edge creatively. But, unfortunately, she was coming close to falling over the edge emotionally. Things were happening too fast, and in 1996 a series of events pushed Björk to the precipice. Her relationships with Tricky and jungle artist Goldie became hot gossip. Then, arriving in Bangkok late one night, Björk was surprised to be greeted by nine TV crews. One reporter refused to take her statement of "no interviews" seriously. As Björk tells it: "This woman kept going live on the air, even though we didn't say yes. She kept saying, 'Oh, Björk obviously doesn't have any time for us and is thinking about other things' - she was being quite bitchy. And then she went to my son, live, in front of millions, she said: 'Isn't it terrible to have a pop-star mom who's so full of herself?' I just lost it. I'm not going to one minute say what I did was right. But it was the third time in my life I lose it: Once when I was six and once when I was 17. I just saw red. Afterwards, when I calmed down, the first thing I did was go to him and say, 'I'm so sorry' He just looked at me and said, 'No, mom, don't worry, I understand. What I don't understand is why didn't you hit the guy with the camera first, and then go for the reporter. Mom, next time think!'" Then, in September, an American fan killed himself after sending Björk a letter bomb that was safely intercepted. All of these events set the stage for Homogenic's depth plumbing.

"A lot of things happened last year,"

Björk says at the cafe.

"I'd been living very

fast for four years. I knew when I left

Iceland I wanted to go on a mission. I was

ready for it. I wanted danger, and I got it.

And it was very satisfying. And then last

autumn I had my kick. Sometimes you've got

all these things inside you and you don't

get them out unless you have stimulation

from outside. And sometimes that stimulation

has to be quite aggressive.

"But you can only do that for so long,

and then there's stagnation. And then the

biggest challenge is to sit still.

So suddenly I had to sit still. And if I could do

that for 10 minutes, which was, believe me,

very hard after four years of 5,000 miles

per hour, then the big things start coming out." If Björk's is world music, it's a world of her own making. Homogenic was recorded in Spain with a British electronica whiz kid, Icelandic string players, and a Brazilian string arranger. "This album, like all things, I started off saying, 'OK, it's time to do something completely different' It's very important to have a target. Of course, you're human, and things develop and take their own forms and shapes - you've got to let them do that. [On Homogenic], the first target was string arrangements and beats, and that was it. I was going to be really military about the fact there'd be no bass line, no other instruments." Björk hasn't strayed far from her original target. On songs such as "All Neon Like" and "5 Years," Mark Bell's drum programs pop and spurt like, well, like Icelandic mud pools and geysers, while the strains of the Icelandic String Octet - eight musicians Björk culled especially for this album - swell and ebb dramatically on "Bachelorette," a haunting, lovely song. Björk uses the beats and bows more as atmospheric elements than as structure; these songs are held on skeletal frames, implied rather than stated. "Musical structure is probably my strongest side," Björk says. "I've always been very fierce about chord structure and song structure. When it comes to arrangement, I love to take risks and experiment. I've had people say they think I'm free-forming through the whole album, and I'm definitely not." Björk describes Homogenic in elemental terms. "For me, this album was going back to basics. On Debut and Post, all the songs were written over a long period, but all the arrangements were done in England over a period of four years where I got introduced to a lot of exciting things. Now it's time to come back to where I'm from. When I say that, I mean maybe more musically than geographically - back home, whatever that means. I decided to start from the beginning and cut all the crap, because it's very easy to keep people's attention with 9,000 different toys. I went down to saying, what are the three toys that are the most important when it comes to noise things? I would say the voice, because we're all experts in the human voice. I think the voice celebrates oxygen, and that's one network in our bodies. And strings have always had a really good impact on me; I think there must be something very similar in strings to our nerve system. And the beat is the pulse, which is the blood, the heart." Björk's confidence in her structures has liberated her vocally. She steps out of the belt, bellow, and warble of her previous albums to croon softly on "Bachelorette," soar mightily on "Hunter," or go Diamanda Galas-style ballistic on the apocalyptic "Pluto." "When I started doing my own records, because my biggest experience was with singing, that was where I felt secure," Björk says. "But in things like songwriting and arrangements, I didn't have the same confidence, so my voice was the boring old matrix not doing anything adventurous, just staying in one place to keep the song together. Then I could experiment with the other things. And now I feel more comfortable with the other things, so my singing voice has gone a bit off-duty. It doesn't have to be the one who gets there at nine."

In her recent book, The Lure of the Local: Senses of Place in a Multicentered Society, art critic Lucy R. Lippard talks about "multicenteredness," how in our mobile society, we may have several places - that function as home. I wonder if that's how Björk feels: equally at ease in the mud of Iceland, in the clubs of London, and in a plane traveling the world. "I like Iceland's being as Iceland as possible," she says. "But then I like being on Times Square and being surrounded with at least 50 nationalities. I believe in both. I was lucky because I could go away. The situation's ideal because you've got home, and then you go and come back and nothing's changed. London is crap. It's a great place to visit, but not to live." Björk is fierce, but not blindly so,

in her love of country. Perhaps having traveled

so much, she realizes how this land formed

of fire and ice, where there's little sun

in the winter and only a few hours of darkness

during the summer, is in her blood.

"I think what attracts me and turns me on

is extremes. And that's probably the best

thing about me and the worst thing about me.

Icelandic people tend to be quite

passionate about things. It's all or nothing.

There's no understatements or maybes.

"Somewhere along the line I made a wish

unconsciously to take as fully part of things

as I could, and that means you've got to be

ready to end periods and start new ones.

And change. And of course it's painful.

But when you plant a wish like that, that you

want to experience and feel maximum, you've got

to realize that that's what comes with

it. We want these 80 or however many years

we get to live to be very colorful and

diverse." That wonder-full embrace of the world is

Björk's calling card, the key to her

whimsical appeal. She may have gotten

that enthusiasm from this country in which

people both know how to party and like to

read a lot. Or she may have gotten it from

her jazz-loving grandparents or her hippie

parents. Or it may just be a gift all her

own that has somehow not been beaten out of

her. If Homogenic captures a period of

free fall, it's because Björk is letting

herself feel the pain, even reveling in it:

"I'm no fucking Buddhist, but this is

enlightenment," she sings on "Alarm Call." That

track is followed on Homogenic by the

explosion of "Pluto" - i.e., death. Afterward,

Björk is in a state of rapture, singing

beatifically "All Is Full of Love," sitting

still for 10 minutes in a hot tub, home again.

|