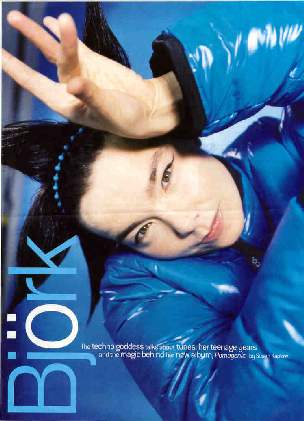

Seventeen 8/97Björkby Susan Kaplow

|

|

How would you describe the sound of your fourth solo album, Homogenic? I'm just trying to be truthful about what 1997 is. I'm talking about all the noicses that most people call ugly in some instances because they're too familiar. I've tried to reorganize them and put a bit of magic there. When you recorded your third solo album, Post, in the Bahamas, you wore headphones with an extralong cord so you could sing and run around on the beach at the same time. Did you do the same for Homogenic?

I kind of got that out of my system the last time. I recorded

Homogenic in a house in El Madronal, Spain, where I could stand on a

balcony that looked out to Africa. I sang in a mixing room with my friends

near me.

You've said in the past that you write most of your songs about your close friends. Who did you write songs about this time? This album is written more for these people than about them. This album is about me losing patience and that life's too short and there's a clock tickin'. Last year an obsessive fan committed suicide after sending a letter bomb to your home in London that, thankfully, was intercepted by the police. Is that why you decided to move and record the album in Spain? I just wanted to get away from it all. Do the things you never have time to do when you're in the city, like go on three-hour walks. You were born in Iceland, a polar country filled with glaciers, mineral springs and volcanoes. Do you think you're an especially creative person because you grew up in awe-inspiring surroundings? I think I'd be the same no matter where I grew up. Thing is, Iceland is a place where if someone needs a house, they go out and build it. If they need food, they hunt or fish for it. Same with art. If they need a song, they go and write it. Art isn't put on a pedestal [in Iceland]. It's part of life - like baking a cake. You went to music school from ages 5 through 15, recorded your first album when you were 11 and attained international fame by the time you were 22 with your celebrated band the Sugarcubes. Did you have any mentors or idols who inspired you? No, I'm not into nostalgia. I've always wanted to write the kind of song that no one has written before. I was always the rebel. They [the teachers in school] were teaching me 300 years of German music and calling it classical. Why couldn't music from other parts of the world be called classical? The headmaster of my music school had me up in his office a lot. Do you still write all your music in Icelandic, your native tongue, and then translate it into English? Yeah, though I can't do interviews in Icelandic. I feel like my grand [grandmother] would scold me and call me a pretentious git [an idiot]. As a teen in Iceland you and your friends created your own art scene. Can you explain? We would get upset [that there wasn't good music on the radio], so we started a pirate station and played our own music - music that you couldn't get in Iceland. Someone would hold their own festival and show all the films that our movie theaters wouldn't show. We were trying to fight the small-town mentality. You were married and had your son, Sindri, when you were 19. As you may or may not know, teen pregnancy is a problem in this country. Many young girls who become pregnant are scared and feel they have nowhere to go. Do you have any advice for young mothers? It's hard for me to understand [the teen pregnancy problem] in this country because I come from a really family-oriented place, where young people having children isn't a big deal. I also had a lot of family members who helped me out with Sindri. Maybe a lot of girls don't have that, so it's a tough one for me to answer. You're 31 years old and often called a child-woman. Yeah. I don't think it's good to stay young forever. But it's important to learn new things. It's about staying alert. You've said you're obsessed with being modern.

This may sound like a contradiction, but I like that in some ways some things

will always be the same. We'll always put on a raincoat when it rains and

a bathing suit when we go to the beach. And there will always be pop music.

At the end of the day, people want to sit down and write about what's

happening and what they're hoping for. It's so natural. |