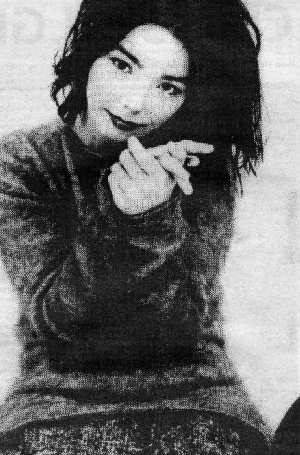

Hotpress 10/8/94Björk on the wild sideInterview by Liam Fay

| ||

|

Amusement arcades, fun palaces, all day cabaret bars, souvenir shops and other elaborate torture chambers churn away at full capacity. For the more adventurous and the stronger of stomach, there are the delights of wet t-shirt contests or cocktail drinking bouts or The Nolans or Frank Carson or The Grumbieweeds or even Roy Chubby Brown. And then, there's the fat people. Thousands of them down by the beach, fat men, fat women and fat children, with their shirts off. You've heard of the Blackpool illuminations? Yeah, well that's when you go to Blackpool and you're suddenly struck by a series of blinding realisations about the sorry state your life is in that you should wind up here. Today, there is an extra dimension to the black comedy. The Queen and Prince Philip are in town to help celebrate the resort's centenary year and to take a ride to the very top of the newly renovated Blackpool Tower. This means that every single fuckwit DJ on the local station, Radio Wave, gets to say, 'they really are their Royal Highnesses now," before melting into a puddle of uncontrollable mirth. It also means that there are cops everywhere and that most of the streets are clogged up with armies of fatties who have swapped their buckets and spades for plastic Union Jacks and I Love Liz hats. It's the charge of the cellulite brigade. Bjork is also here. Not on the pier or amid the monarchy junkies but here in the generel vicinity, and that's enough. The strangest woman in pop breathing the same chip-grease tainted air as HRH. It's almost too surreal to be true. "I feel sorry for her," Bjork will muse later, even more bizarrely, while staring at a photograph of Mrs. Windsor in an evening paper. "It's a hard cross to bear. That sounds an hilarious thing to say but, no matter what job you do, if you're forced into it from the day you're born, it has to be a cross. It's the complete opposite of freedom. And for me, that's the only thing that life is about. Freedom." Backstage at The Empress Baltroom in Blackpool's famed Winter Gardens, at around 6.30 in the evening, Bjork is sloping about and sipping from a steaming hol honey drink of some sort. "My grandmother's recipe," she giggles, whenever anyone asks exactly what it is, their nostrils intrigued by the exotic, sugary and strongly alcoholic aroma wafting from the paper cup in her hand. Bjork and a thirty strong group comprising her band, a squad of record company types and a sizeable battalion of f riends from Iceland have spent eight sweaty hours in a tour bus travelling here from London. Everybody else appears drained and weary but Bjork herself is literally skipping about the place, standing still only occasionally to stare down from the side balcony at two roadies who are engaged in a very aggressive game of Frisbee. When someone blasts out a large gust of dry ice which obscures both players but not their flying saucer, she shrieks with hysterical laughter and stamps her foot several times. "I'm terrified of getting bored," she tells me later. "I always make sure that I've got nine things, at least, to do. I panic if I think I'm going to have to twiddle my thumbs. I've tried lying around the house doing nothing but I hate it. It's my worst point but it's a good point as well 'cause you get a lot of things done. I like action." Today, this perpetual motion mechanism is clad simply in a tight, lime-coloured mini dress. By what have become accepted Bjorkian garb standards, it's a surprisingly conventional outfit. There is, however, one stylistic sting. Her feet are shod with a pair of football boots, complete with the full compliment of studs. "I got them during the World Cup," she explains. "I went out to get some for my kid and I bought some for myself as well. Both of us got obsessed with the World Cup. To be honest, I think I tell more for the whole emotion of the thing, people crying and everything. I was just watching it as a human experience. I love to see people going mad like that. They went mad in Ireland too, didn't they? I love that. It's incredible. My kid is in Iceland now with his dad, on holiday, and I'm sure he's playing football. He became a football fan this Summer so we watched all of the World Cup together. He watched the football and I watched the humans." Bjork's studs are playing havoc with the wooden floor in The Empress Ballroom, especially where she stamps one of her feet which she seems to do quite a lot when she's amused by something. She really is a quere card. Very skittish, very whimsical and very, very giddy. Not at all what you'd expect from a twenty-eight year old pop Star. "I like being silly," she says. "it's the best way to be for me. I prefer bad jokes to good ones. I'm obsessed with bad jokes, the badder the better." Indeed, the lasting impression of Bjork is of a toddler playing at being an adult. She can be saying something that is, by her own lights, perfectly mature and sensible but it will be curiously undermined by her demeanour. Like a lot of nippers, she wears a look of a permanent perplexion that seems to be only a lip curl away from both tears and laughter. She also has the attention span of a senile goldfish. During our interview in a tiny, unventilated room oft The Empress production office, we are interrupted briefly by the arrival of some herba tea. In the split second that it takes for me to turn and accept my cup, Bjork seems to forget that I'm even there. She picks up my note pad from the bench between us and starts flicking through it. She also begins to linker with my tape machine. And then there's her eh, personal habits. Bjork's hands constantly darf around all over herself like searchlights around a prison compound after the alarm has been raised. It's as if she's just been given her body for the first time and is unsure whether or not it fits. Her nose, knees and shoulders are her chief ports of call but there isn't a locale on her person that she doesn't visit at least once during our encounter for a scratch, a poke, a tug or perhaps even a combination manoeuvre involving all three. At times, her fidgeting gets quite contortive. There was a particular moment when I thought that her grimace of fierce concentration was a response to one of my probing queries but then realised that she actually had both arms twisted behind her back at the time and was straining hard to massage a particular point on her upper spine. Crouched on a Polyprop chair, her left shoulder strap keeps slipping down her arm and her right hand repeatedly flits across to replace it. Observe closely, however, and you'll see that the reason this continually happens is that she is forever twitching her left shoulder so as to force the strap to slip oft. I am of the firm belief that if Bjork had the wherewithal to play pocket billiards, she would never leave the house. Of course, to view Bjork is a quirky, flighty Icelandic imp is only to see part of the story. As she proved beyond doubt with last year's phenomenal Debut album, she's no daw when it comes to compressing the masonry of her loose-slates personality into music that is beguiling, affecting and unique. With only the limited firepower of the One Little Indien label behind it, initially at least, worldwide sales of Debut quickly surpassed the two million mark and it's still a major mover at the cash desks. More importantly, in a way that cannot be conveyed through retail figures alone, Biork is now a STAR, adored by millions, fêted by her elders and envied by most of her more highly-touted contemporaries whose work ehe leaves for dead on pop's mezzanine floor. Right now, in career terms, Biork is swinging from the rafters. She has also become one of the few genuine icons of the '90s. Her striking features supplying the ideal canvas for a series of looks and images that instantly imprint themselves on your brainstem. She attracts wannabees in a way that no-one since Madonna has done. At the Blackpool show, the arena is alive with Biork clones of sundry shapes, sizes and skin colours. The most impressive being the knee-high, seven or eight year-old girl assiduously attired in early Bjork bring-and-buychic: fake fur-sleeved top, velvet mini-skirt, woollen tights and platform shoes, cones of hair sprouting out of the sides of her head like bangers from Desperate Dan's plate of mash. Characteristically, Bjork herself is unfazed by such devotion. "The onty thing I can do is do what I'm doing as best as I can," she asserts. "I've been doing things in Iceland for years before this. All I've got is my instinct, really. There's not a lot of logic in my head. It's an attitude thing. Yes, there are times when I don't know where to go but that's life. I wait for a week and then I know. "Of course, I'm honoured when peopie like what I do but I've been making music long enough to not feed off on it. At the end of the day, the only person who knows what you're doing is yourself.

Bjork's sense of defiant confidence has been hard won and stems from the sacrifices she has had to make to get where she is now. For a long time, she resisted any suggestion of a permanent move from Reykjavik to London. But last year she reluctantly decided to bite the bullet and she bought a house near Little Venice in West London where she and her son, Sindri, now live. "It took a lot for me to swallow my pride and move to London because I'm as patriotic as people can get," she insists. "Going on my Mission, it didn't make any sense to do it by fax from lceland. After thinking about it, I realised that, anyway, I've travelled with my kid since he was one, and he's still as lcelandic as an icelandic person can get but very international al the same time. "When I first moved here with my kid, I was very aware that he might hate it. I knew we might have to go back and that I would have to do other jobs. I was prepared to do that if he didn't like it because want him to remain very much an icelandic person but, fortunately, he loved it." For Bjork herself, however, the transition was far from easy. She admits that there were several nights last year when she cried herself to sleep with homesickness. "Where I come from, it takes years to get truly intimate with people," she explains. "You don't say you're friends until you've known them for ten years, delivered their babies, gone to funerals with them and all that bollocks (laughs). I met a lot of people in London but I dealt with them not as friends but as mates. Is there a level of difference there in English? I thought that I would never have real friends here." Sooner than she had ever expected though, she found that she had developed a deep attachment to those London mates. "I went to iceland at Christmas and surprised myself iri that I missed London," she proclaims. "I had decided in my head that Iceland will always be the place where all the people I love are and that I would be on this mission abroad with all the foreigners for a while. A lot of the people I've met in London are not English, they're foreign too and I can really relate to them in a lot of ways. They think like me. Coming back was a really happy feeling." Like many irish people who have emigrated to London before her, Bjork was distressed to discover that, by and large, British people don't know how to booze property. When some of them suggest that you meet for a drink, that's exactly what they mean. You meet, have one drink and then go home. What a shower of wussies! "Yeah, definitely, some of them are very strange like that," says Biork, her girlish giggle swelling to a barnyard guffaw. "There's a lot of similarities between Iceland and Ireland. All the poetry, I guess, and the literature and the drinking. Do you play chess over there? Chess is massive in Iceland. There's a lot of chess-playing and telling stories while you're getting hilariously drunk. Falling asleep on the chess table is very much part of Icelandic culture." Bjork says that she's still prone to embarking on massive skites in London, often with British friends who share her passion for the grain and definitely whenever some of her Icelandic buddies are in town. "When I get drunk, I get drunk, there's no doubt about it," she stresses. "Vodka by the bottle. That's the kind of culture I come from. We don't sip drink, we fucking drink it. You go all the way, otherwise you're a wimp. It has a lot to do with the weather. You're always either very sober or very drunk. There's no room for the in-between stuff. "I used to love drinking during the blizzards in Iceland. You'd dress really well and run between bars getting really pissed on slammers. Slammers are the best drink when there's blizzards. Then, we'd go out and roll in the snow. I'd be lying if I said I didn't miss all that. " By her own definition, Bjork is an extremist. She likes to take things too far. Nowhere more so than in her personal life. "I don't like in-between stuff," she says, repeating one of her favourite phrases. "I love really, really sweet stuff like chocolate cakes and then I love curry, vindaloo, do you know what I mean? I guess I'm an over emotional person. I'm very, very happy or I'm very, very this or very, very that. Always two verys." But doesn't she find this kind of big dipper existence a bit exhausting? Are the highs worth the lows? "Yeah, because even when I'm miserable it's over in five minutes," she replies. "It's like (sticks out her chin, bulges the veins in her neck and clenches a fist) brraaaaaagh! And, then it's over, I go all the way to the bottom but then I go (the fist now soars skyward and she leaps off the chair for added emphasis) whooooooosh! That's a very Icelandic thing. A Viking, hardcore, don't-feel-sorry-for-yourself attitude. When I laugh, I laugh really loud. You have to hurt yourself laughing or it's no good." There are, nevertheless, reports that sometimes Bjork hits rock bottom with such force that she finds it almost impossible to escape from the wreckage. When she split last Christmas with her DJ friend, Dom, the man who along with Sindri is offered "chunks of love and thanks for inspiration, endless suggestions and understanding" on the sleeve of Debut, she is said to have gone off the rails, emotionally, to a point that seriously worried those closest to her. Bjork herself is reluctant to elaborate on the details. She merely offers the information that she's "got a lover going on at the moment" and then breaks into a fit of giggles and a ferocious bout of knee scratching. She also firmly rejects the suggestion that she is, in any way, addicted to the drama of emotional crises. "I'm not a drama person," she insists. "I very, very rarely argue with people. Once every live years or so, I think (laughs). Well, it used to be once every five years. This year has been very drastic. There's been a tot of people trying to force down my throat things they think they know all about. They don't realise that I'm doing something for the first time and I want it to be done different from before." Neat change of subject there, I think you'll agree. Björk is very pointedly vague about who these "people" are but, given the success of Debut, there is inevitably pressure from the vast organisation that now surrounds her to replicate it next time 'round. "It's nothing mean," she says. "It's just that I've got a lot of people around me. A lot of older people just want to do it one more time the same so I've got to push them. There's been arguments this year but, in general, I don't really argue. People will only force you into things if you let them. I'm not going to let them." On the face of it, Bjork Gudmundsdottir had a very unusual childhood. She grew up in a sort of Icelandic hippie commune that comprised eight adults turning on and tuning in beneath the eaves of one modestly-sized apartment. They did not, however, drop out. These were hippies who worked for a living. "It wasn't as bohemian as it sounds," Bjork insists. "They all had proper jobs. There was never any unemployment in Iceland until about two years ago. My mother made furniture at one point but she also worked in an office doing Computers. My father was a full time blues musician. Everybody worked. Everybody got up early. In Iceland, even the hippies are workaholics." Nevertheless, there are some things common to hippies the whole worid over, and Bjork remembers her cohabitants smoking their fair share of dope during her formative years. It's an activity which she now personally despises. "Different things suit different people," she says. "I personally can't deal with hash. I'm clautrophobic and I'm obsessed with oxygen. I can't deal with smoke or pollution of any kind. I'm not very big into drugs. I like my drinking too much." Equally, Bjork grew up to hate the music which was constantly being pumped into her head by her parents and their friends. "It was the early '70s and they were listening to this psychedelic crap all the time," she recalls. "There was always lots of blues around too. Jimi Hendrix, Cream, all this stuff. They gave me a love of music because all these people really loved this music but by the time I was seven I was completely bored with guitar and drums. I then got into jazz and classical and choral music, and folk music. My grandparents used to go see an Irish band called The Dubliners? Do you know them? My grandmother loved all these kinds of music that were different from the hippie stuff. I was very lucky to have all this stuff going on around me." With the help of her mother, Hilda, Bjork recorded her first album in 1976 when she was only eleven years of age. Entitled simply Biork Gudmundsdottir, the record featured Biork's interpretations in a variety of styles of songs written by some well known Icelandic composers (well-known in lceland, that is). It went double platinum in Iceland and is now a much coveted collector's item. Bjork says that she didn't much care for all the attention which her recording accomplishment brought her but she had already grown to love the process of making music. She played in dozens of bands during her teenage years (including an all girl punk combo with the charming moniker of Spit And Snot!) and began writing her own material, some of the earliest snippets of which were eventually to surface, many years later, on Debut. When she was fifteen, Bjork left home, determined to carve out an independent life for herself. Music was still her abiding passion but she had to find some way to put chocolate cake on the table so she took a succession of jobs that included stints in a fish factory, a Coca Cola bottling plant and a record shop. In her late teens, she joined an ahem, "hardcore existentialist jazz punk" band called Kukl. Having toured extensively in Europa all Summer, she and the rast of the Kukl crew returned to Reykjavik in the Winter of 1986 and immediately fall in with Bad Taste, a radical arts collective which ran a record store cum bookshop. It was very soon afterwards that Bjork was arrested for the first time. She spent a night in a cell, having smashed the windows of a local disco 'because it was full of boring people.' "We were on a bit of a mission, trying to change the world, I guess, " she recalls. "We spent a lot of time in the police station actually. We'd have these long conversations with the policemen, trying to open their eyes. In the end of the day, it was just a laugh. We liked to annoy them." Bjork's boyfriend during these days was a guitarist called Thor Eldon. In 1987, with him and a few like-minded Bad Taste poets, Kukl grew into The Sugarcubes. That Same year, Bjork and Thor also had a son, whom they named Sindri. The Sugarcubes was never really much more than a lark for all concerned and nobody was more surprised than themselves at the impact they had not only in Europe but in the States too. "It was a hobby really, " Bjork insists. "We'd all got drunk at weekends and write these weirdo pop songs and then when we had enough we could go on holiday as The Sugarcubes. It was just a group of friends travelling all over the world and thinking, 'this is crazy'. Nobody expected to last even as long as it did." Since the official Sugarcubes split in 1992, Bjork has remained in regular contact not only with Thor but with virtually all the former members of the band who, she says, are still very active in Bad Taste, "writing, recording and laughing a lot." None of them rasant her success, she says, because they would be even more loathe to leave Iceland than she herself was. "I was over there five times last year but mostly only for two or three days," she states. "The fast thing people are going to say to me is fuck off. The only people I meet are my real, true good friends and we just talk about everything like we used to, silly things. " Similarly, she is adamant that having a lot of money, as she now most certainly does, has not caused any tensions in her relationships with her family and friends. "Money just saves time," she avers. "It means I can do more of the things I love to do and less of the things I hate to do. All my family are very hard working people. They're electricians, carpenters, bricklayers. My mother always worked. Now, that I have some money, she doesn't have to work but she does. She's actually studying homeopathy, making her lifelong dream come true alter all these years. We don't have the class system in Iceland but we were a working class type of family. Our money came from work. That's what I'm used to, work. "If I didn't have a job or any money tomorrow morning, I'd go down to the market and sell junk or whatever. Self-sufficiency. I make fun of because it's pathetic being such a workaholic but it's what I was brought up with. You have to learn how to manage. And if you have, you can manage. But it doesn't mean that you stop working or that you change as a person. Not for Icelandic people." In the teeth of all the Blackpool odds, the Bjork show is a stunner. Live, her songs are transformed into something much more sinuous and muscular than on the album. And, there is the added gesture of Bjorks own curiousty compelling stage presence. After her appearance at Féile next weekend, she starts concentrating on the second album, the recording of which is set to begin in early October. Most of the songs on Debut were composed on a Casio keybord and she continues to work that way. She insists that there are still "hundreds" of songs in her cellar, awaiting their moment in the sun, but she is determined to write completely new material for the next collection. "The last album was like pieces from my diary or my photo album, " she attests. "They were all about the past and now I want to show you things from my new diary, my diary of the last two years. There'll be some mix of emotions, happy, sad, confused, all that bollocks, but they'll be new. " At this point, the plan is that Bjork will co-produce this time with Nellee Hooper, the dance guru who gave Debut its hefty rhythmic edge. Nellee is one of the people that Bjork admires most, alongside such notables as David Attenborough and Albert Einstein. "I've always been a bit soft on scientists and men who can work miracles with their brains, " she laughs. "And, oh yeah, my grandmother. She's sixty eight and she goes camping and paints and just lives life large. I want to be like her. I'm in a situation now that I'll probably never be in again, I can go into a studio and I don't have to worry about the bill. I bought myself a computer the other day that I can draw pictures on to siut the music. I don't have to fight so hard for things now but I might again. And, when I do I pray that I'll be as self-sufficient as my grandmother." Who does Bjork pray to? "I've got my own religion, "

she concludes, giving her nose a final scatch, poke and lug before heading off for a soundcheck.

"Iceland sets a world-record. The United Nations asked people from all over the world a series of questions. Iceland stuck out on one thing. When we were asked what do we believe, 90% said, 'ourselves'. I think I'm in that group. If I get into trouble, there's no God or Allah to sort me out. I have to do it myself."

| ||